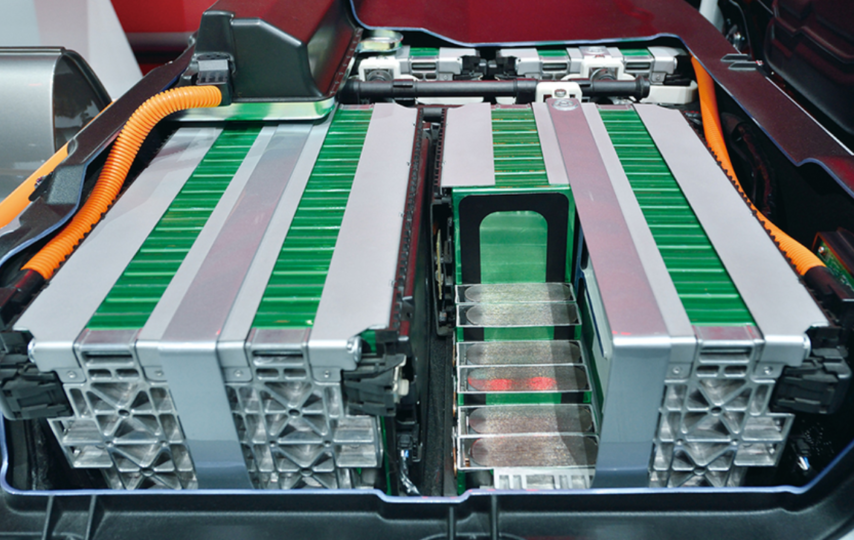

Rechargeable batteries power nearly every modern gadget—phones, laptops, wearables, cordless tools, cameras, portable speakers, and countless accessories. When people evaluate a device, they notice the screen, the processor, the camera, and the features, but day-to-day satisfaction often comes down to one practical question: how long the device runs before it needs to be plugged in again.

Over time, most users observe the same pattern. A device that once lasted a full day starts needing a top-up in the afternoon. A tool that used to finish a job on one charge now needs a battery swap. The device still works, but the usable runtime slowly shrinks. This change is usually not mysterious software behavior—it is the combined effect of battery aging and battery degradation.

It helps clarify why runtime changes even when a battery appears to charge normally, and which usage habits have the greatest impact on long-term usability.

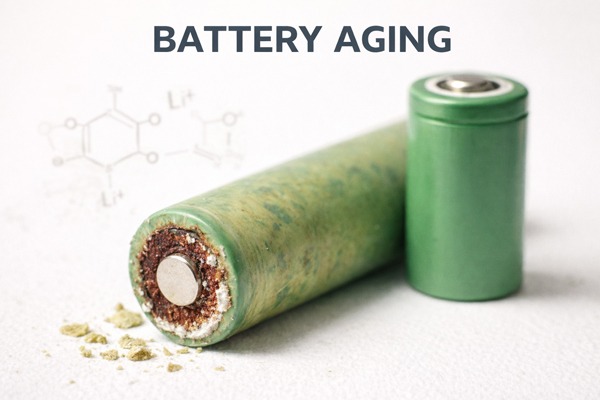

Battery aging is a time-dependent process

Battery aging describes the gradual, time-based changes that occur inside a rechargeable battery from the moment it is manufactured. Even when a battery is not being used, slow chemical reactions continue in the background. When the battery is used, additional wear occurs as materials repeatedly store and release ions during charging and discharging.

In practice, aging happens in two overlapping ways:

Calendar aging: changes that occur simply because time passes, influenced strongly by temperature and storage state of charge.

Cycle aging: wear that accumulates as the battery is charged and discharged, influenced by depth of discharge, charge rate, discharge rate, and heat.

Because both mechanisms operate at the same time, a lightly used device can still lose noticeable runtime after a few years, while a heavily used device can lose runtime sooner.

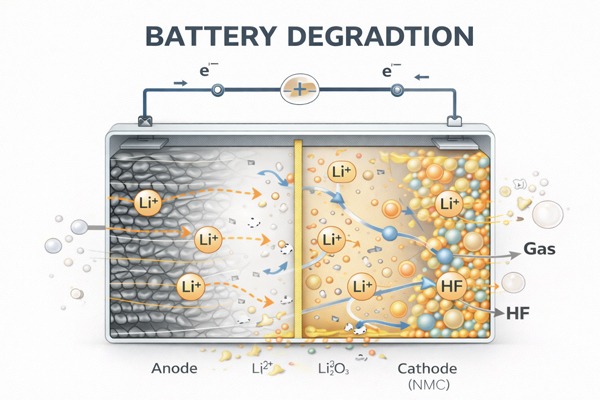

Battery degradation is the outcome you can measure

Battery degradation is the observable performance decline caused by aging. Aging is the internal process; degradation is the external result. Degradation usually shows up as a mix of:

Capacity fade: the battery stores less usable energy than it did when new.

Resistance growth: the battery wastes more energy as heat, and voltage drops more under load.

Reduced power capability: the battery struggles more with peak demand.

These changes are permanent. A battery can sometimes appear “better” after calibration or software updates, but those steps typically improve measurement accuracy, not the underlying chemistry.

Why runtime shrinks before a battery “fails”

Consumers often think batteries have two states: good or dead. In reality, most batteries spend a long time in the middle—still functional, but gradually less capable. Runtime can shrink for two main reasons.

First, capacity fade reduces the total energy available. If a battery originally stored 100 units of energy and now stores 80, the best-case runtime is already lower.

Second, resistance growth reduces delivery efficiency. When internal resistance rises, more energy turns into heat during both charging and discharging. Under load, the battery voltage sags more. Many devices have minimum voltage thresholds for stable operation. If voltage dips below that threshold during a power spike, the device may throttle performance, shut down early, or hit “low battery” sooner, even if some capacity technically remains.

This is why degradation often feels worse than a simple “20% capacity loss.” The device may become less tolerant of peaks, which makes daily behavior look more dramatic.

Fast charging and supercharging: what actually matters

Fast charging is not automatically harmful. Many electronics use staged charging profiles, current limits, and temperature monitoring to reduce stress. However, frequent high-current charging can accelerate aging when it repeatedly creates elevated temperature and holds the battery near full charge for extended periods.

A simple, practical way to think about it is:

Fast charging is most stressful when the battery is warm, the environment is hot, or the device is being used heavily while charging.

Slower charging is gentler, especially for topping up in cool conditions.

For readers who want a clear breakdown of runtime (what it means, how it is measured, and why it differs from capacity numbers), see this guide on how long a device runs between charges in everyday use.

High demand makes degradation more noticeable

Two batteries with the same remaining capacity can behave very differently depending on what they power. High-demand electronics—bright screens, radios, cameras, gaming workloads, motors, and inverters—pull higher current. Higher current magnifies voltage sag and heat generation, so resistance growth becomes more visible.

That is why users often notice aging faster in:

Smartphones during heavy camera use, navigation, or gaming

Laptops under sustained CPU/GPU workloads

Cordless tools or accessories with motor loads

Devices used outdoors in cold weather (where voltage sag is naturally worse)

A battery can be “okay” for light tasks yet feel weak during heavy tasks, even with the same displayed percentage.

Heat is the biggest accelerator of aging

If you only remember one factor, remember temperature. Higher temperature speeds up chemical side reactions that permanently change battery materials. Heat can come from the environment (hot rooms, sun exposure, car interiors) or from inside the battery itself (resistance heating during fast charging and high-power use).

The most aging-intensive patterns typically involve repeated sustained heat, such as:

Charging while the device is under heavy load

Frequent high-power discharge (for example, continuous performance modes)

Leaving devices in hot locations for long periods

Repeated rapid charging sessions that keep the battery warm

Short heat events are less damaging than repeated, sustained heat over weeks and months.

Batteries age even when not used

It surprises many people that batteries age in storage. Calendar aging continues even if a device is turned off and sitting on a shelf. Storage conditions matter a lot:

Heat accelerates aging dramatically.

Storing at very high charge for long periods can increase stress.

Storing at very low charge for long periods can risk over-discharge in some systems.

For electronics that will be stored for a while, moderate charge and cooler storage conditions generally reduce long-term wear.

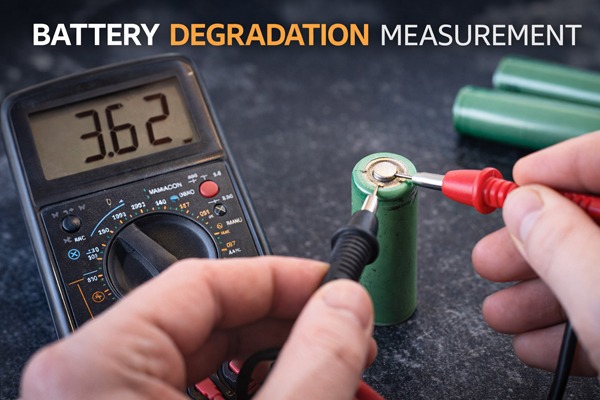

How to interpret runtime decline in consumer electronics

A single measurement rarely tells the full story. Runtime changes depend on workload, temperature, and settings. A better approach is to compare like-for-like behavior:

Same brightness and connectivity conditions for a phone

Similar workload for a laptop

Similar job type for a cordless tool

If runtime keeps trending down under similar conditions, it is a sign that degradation is accumulating.

It also helps to separate “runtime decline” from “sudden failure.” Gradual decline is expected. Sudden failure is often related to damage, manufacturing defects, extreme temperatures, or safety events—much less common than normal aging.

Practical habits that preserve long-term usability

No habit stops aging, but a few habits reliably slow it in consumer electronics:

Reduce sustained heat exposure (especially hot storage and hot charging).

Avoid making rapid charging the default when slower charging is convenient.

Avoid leaving devices at full charge for very long periods when not needed.

Prefer moderate cycles over frequent deep discharge when possible.

If storing a device long-term, keep it in a cooler environment at a moderate charge.

These habits are not about perfection—they are about reducing repeated high-stress conditions that compound over time.

Conclusion

Battery aging is the time-dependent chemical process that occurs inside rechargeable batteries. Battery degradation is the measurable performance decline that results. Together, they explain why real-world runtime shrinks gradually even when a device still seems to work normally. Understanding the capacity-and-resistance story behind runtime helps consumers interpret changes accurately, set realistic expectations, and adopt habits that preserve usability.

FAQ

What is the difference between battery aging and battery degradation?

Aging is the internal chemical process over time; degradation is the observable loss of capacity, efficiency, and power capability caused by that process.

Why does runtime drop even if the battery still charges to 100%?

Because a battery can charge normally while storing less usable energy and delivering it less efficiently under load.

Do batteries degrade if they are not used?

Yes. Calendar aging continues during storage, especially under high temperature and extreme charge levels.

Does fast charging always shorten long-term performance?

Not always, but frequent fast charging can accelerate aging when it repeatedly produces heat and keeps the battery near full charge.

What is the biggest factor that speeds up aging in consumer devices?

Sustained heat exposure—during use, charging, or storage—is one of the most consistent accelerators of long-term aging.